Introduction

The Butte Creek Floodplain Reconnection and Channel Restoration Project will restore over two miles of floodplain and side channel rearing habitat for juvenile salmonids. The project covers the Honey Run unit of the 287-acre CDFW Butte Creek Canyon Ecological Reserve, which was acquired from a gravel mining company after the flood of 1986. Butte Creek is one of only three Central Valley streams that has a population of Central Valley Spring-run Chinook Salmon. The project reach is immediately downstream from the Spring-run spawning grounds in Butte Creek Canyon. This section of Butte Creek is a highly disturbed landscape following nearly a century of gold dredging and gravel mining that extensively manipulated the floodplain and rerouted the channel.

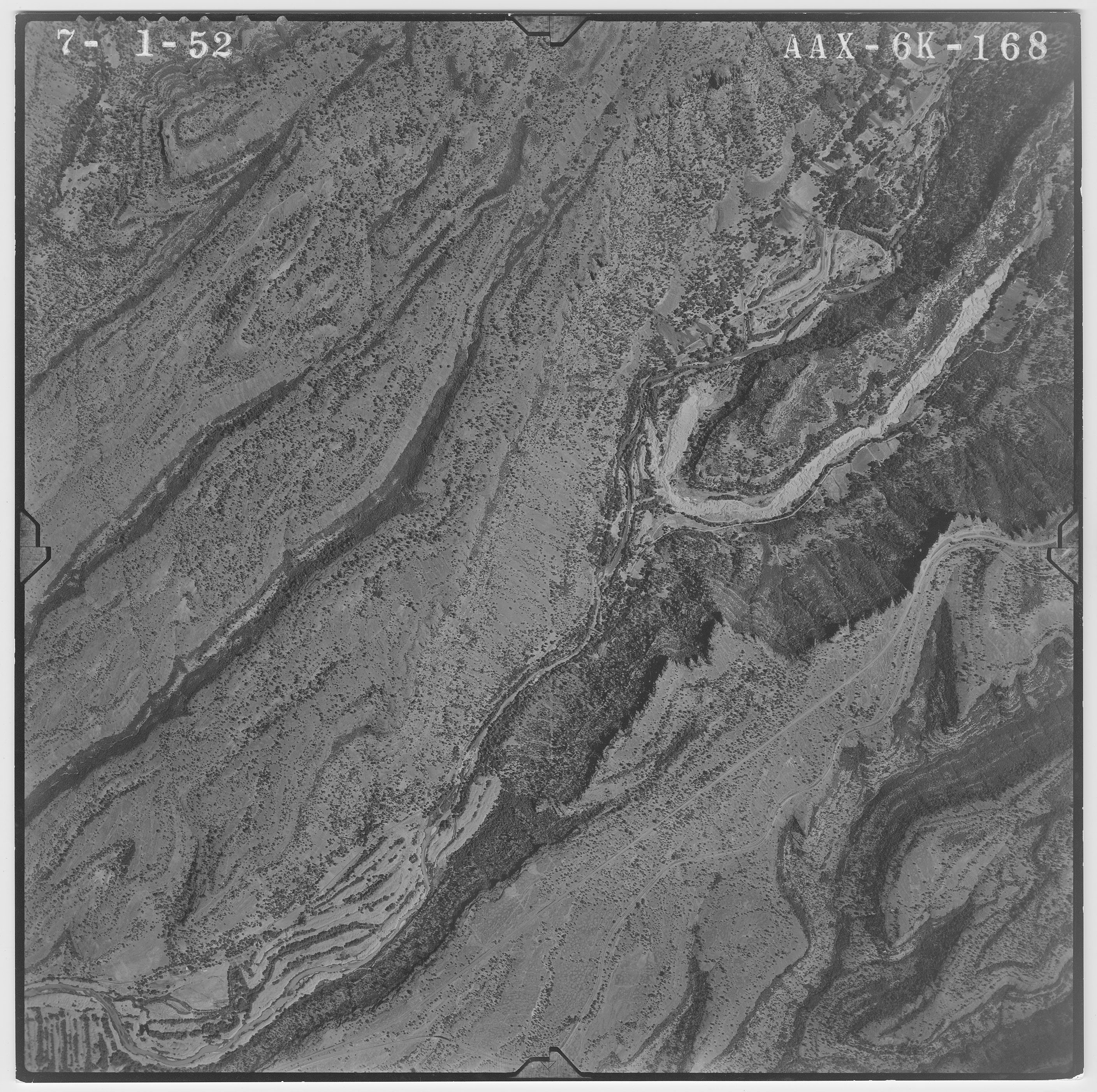

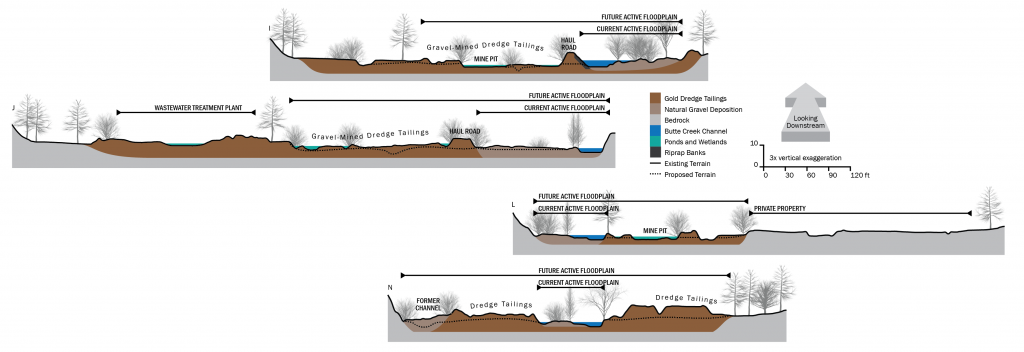

Gold dredging occurring between 1902 and 1949 left piles of gravel tailings and an inverted floodplain soil profile ill-suited to high quality riparian forest. Subsequent gravel mining of these areas from the 1950s through 1970s created deep off-channel pits that create stranding, temperature, and predation hazards for salmonids. The project seeks to (a) expand the floodplain with a restored natural soil profile and healthy floodplain forest; (b) improve hydraulic connectivity between the river channel and this restored floodplain habitat; and (c) increase the effective channel length while creating side-channel rearing habitat for spring-run Chinook salmon.

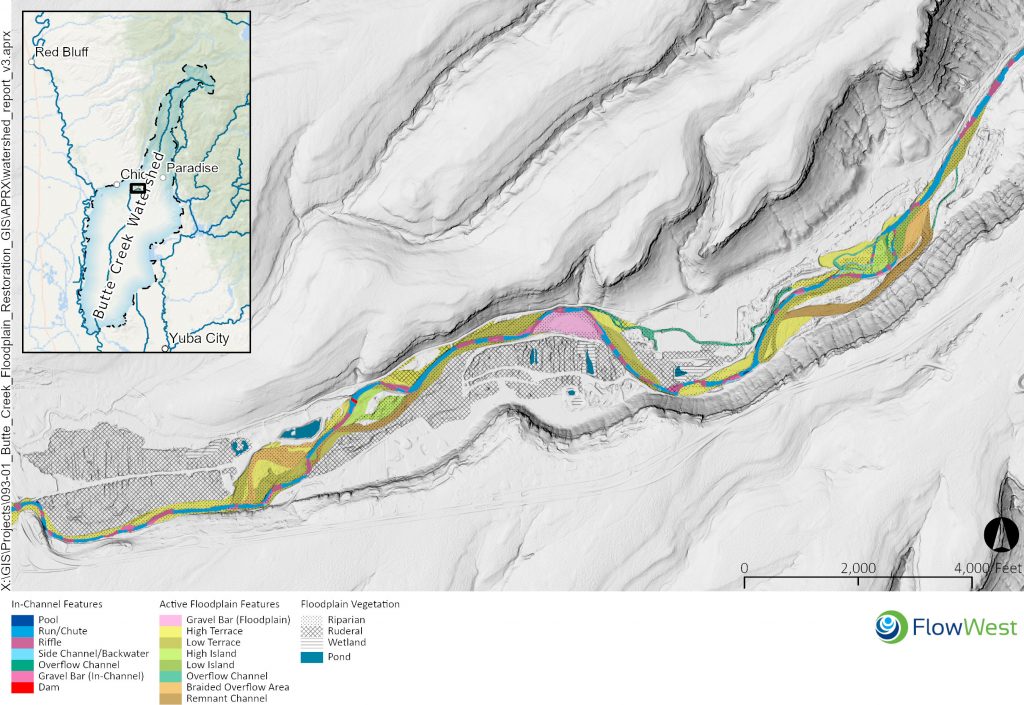

The Friends of Butte Creek team evaluated aerial photos, hydraulic model results, lidar data, and channel geometry to select promising opportunities for restoring floodplain areas, restoring remnant side channels and reconnecting these areas to its floodplain. Project sites are in the historic Butte Creek floodplain and side channel depressions, where restored channels and floodplain improvements are more likely to persist into the future.

The lower reaches of the rearing areas of Butte Creek are a mixture of disturbed landscapes previously mined for gold, gravel and rock. The disturbance happened over a 100-year period from the 1849’s to the 1950’s. Activities included small to very large mechanical manipulations of the floodplain. Large scale dredging equipment and modern gravel extraction tools literally turned the entire floodplain profile upside down. Butte Creek was more-or-less in the way of the various mining operations and was pushed and diked from one side of the floodplain to the other. As the gravel extraction ended in the 1950’s, the land was left with numerous tailing piles (mining tailings), many large dredger ponds, failing roads and bridges scattered across the area. Most recently much of the privately held gravel extraction area was turned over to the CDFW’s Wildlife Conservation Board (WCB) which created the CDFW Butte Creek Ecological Reserve. This 287-acre reserve covers the floodplain from Highway 99 to approximately one mile south of the Honey Run Covered Bridge Park. In addition to this public land, the Butte Creek Ecological Preserve (BCEP) is contiguous upstream of the WCB reserve and adds 93 acres to the protected floodplain of Butte Creek. Formerly managed by CSU Chico Research Foundation, this preserve was transferred to the Mechoopda Indian Tribe of Chico Rancheria in 2022.

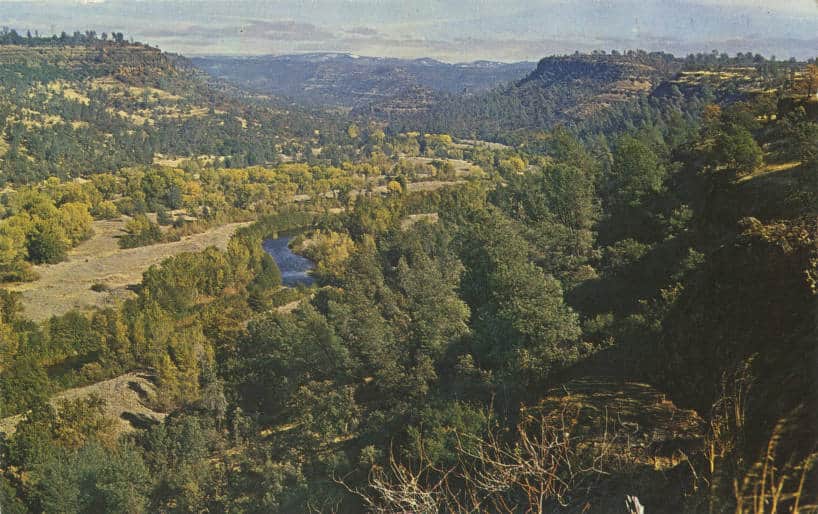

The wide riparian corridor, confined within Butte Creek Canyon, is highly disturbed by a history of gold dredging and gravel mining. In addition to gravel-bedded river channel areas vegetated with riparian woodland, a significant portion of the floodplain is occupied by gold dredge tailings that have been subsequently gravel-mined. These areas are isolated from the active channel, devoid of native vegetation, and contain large areas of seasonal and perennial standing water.

Source: CSU Chico Northeastern California Historical Photograph Collection

Source: CSU Chico Northeastern California Historical Photograph Collection (sc29540)

History

The history of mining in this area began during the Gold Rush in the mid-1800s on lands previously utilized and managed by the Mechoopda and Mountain Maidu Indian Tribes. Gold mining initially occurred on the reach between Centerville and Helltown, starting with placer mining and then transitioning to hydraulic mining and drift mining of Tertiary gravels. The use of power shovels and washing plants began in the early 1900s. Dredging operations took place from around 1902 to the early 1920s, then again in the 1930s, and finally from 1945 to 1949 (Clark, 1976). Typical outcomes of these dredging operations include a reversal of the floodplain profile. Dredges excavate soil material from the top down, beginning with the coarse surface gravels and ending with finer materials including clays that were underlying the gravels. Depositing the tailings in reverse order, the finer materials end up closer to the surface, creating a layer of fines overlaying highly permeable coarse gravels. As described by Kondolf and Williams (2002):

Dredges move across the landscape on a pond of their own creation. As the head of the dredge chews into the floodplain, the tail end of the dredge disgorges the larger cobbles and gravel into piles of “tailings” at the other end of the pond. In this way, the dredge works the pond across the floodplain, leaving [a] characteristic series of elongated piles. . . . The finer sediments are sluiced for gold within the dredge and discharged into the pond, where they settle to the bottom, to be covered later by the tailing piles as the dredge moves along. As a result, the alluvium is inverted; the soil and fine-grained sediments normally at the surface and interspersed through the alluvial sediments are buried, leaving barren piles of relatively uniform cobble across the landscape (Kondolf and Williams, 2002, p. 66).

Butte Creek was also diked and its channel moved to the side of the floodplain to make way for gravel mining operations. Piles of mine tailings were deposited in the floodplain, creating poor quality habitat. Pits and ponds, dug below the water table such that they fill with water, have been left in place. Not only do these features pose a stranding hazard for fish, but they also have significant and potentially deleterious geomorphic impacts: located adjacent to the active channel, they can readily be captured by the channel during high flows, which occurred in the project site during the floods of 1986. In general, Butte Creek along the project reach is highly unstable and prone to jumps, channel avulsions, and cutoffs during high flows.

The adjustable map above shows air photos from 1951 (B&W) and 2021 (Color)

Fisheries

Butte Creek is one of only three Central Valley streams that has a population of federally and State threatened CV Spring-run Chinook Salmon (Spring-run). Butte Creek is also habitat for threatened CCC Steelhead (steelhead). CDFW has specifically identified portions of Lower Butte Creek as a high priority for assessment due to ongoing poor habitat, water quality and quantity concerns and recorded observations of mortality of both upstream migrating salmon and downstream migrating juvenile salmon and steelhead.

Butte Creek has also been identified as a priority area for salmon and steelhead habitat restoration under the CVPIA Near-term Restoration Strategy (NTRS). Butte Creek juvenile salmonid habitat restoration as related to survival is identified in the NTRS as Action 7: “Improve survival in Butte Creek in downstream areas.” The Project would address NTRS Action 7 by restoring over two miles of historic juvenile salmonid floodplain and side channel rearing habitat along Lower Butte Creek that was debased by intensive gravel and gold mining in the late 1800s early 1900s. Salmonid growth associated with floodplain habitat has been shown in several studies to increase survival into adulthood (Sommer et al. 2001, Sommer et al. 2005). As juvenile rearing habitat is restored throughout the Lower Butte Creek floodplain, chances of survival for juvenile salmonids on their way to the Pacific will increase due to better habitat (for feeding and cover) early in their journey (Limm et al. 2009).

Along with restoring up to 320 acres of floodplain habitat, the Project would create or improve hydraulic connectivity between the river channel and this restored floodplain habitat. In addition, this area of the Butte Creek meets Reclamation’s goals for their CVP Habitat and Facility Improvement Program whose main aim is to protect, to restore, and to enhance fish, wildlife, and associated habitats.

In Progress

Existing Conditions Site Assessment (Watershed Report) – January-April 2024

A watershed assessment was conducted at Butte Creek from January to April 2024. This comprehensive evaluation aimed to analyze the current state of the watershed, focusing on water quality, habitat conditions, and biodiversity. The assessment involved collecting data on various environmental parameters, including water temperature, pH levels, sedimentation, and the presence of pollutants. Additionally, the study examined the health of aquatic and riparian ecosystems, identifying key species and potential threats to their habitats. The results of this assessment are expected to inform future conservation efforts and sustainable management practices for Butte Creek.

Existing Conditions Assessment Detail Maps Page 1

Existing Conditions Assessment Detail Maps Page 2

Existing Conditions Assessment Detail Maps Page 3

Existing Conditions Assessment Detail Maps Page 4

Field Survey

A field survey was performed using the following equipment:

- GNSS receiver (rover): Trimble R10

- Data collector: Trimble TSC5

- Echosounder: Seafloor Hydrolite-DFX incl. 30/200kHz transducer

- For topographic data, R10 was mounted on 2m rangepole

- For bathymetry, R10 mounted to Hydrolite kit pole (transducer on bottom) which was in turn mounted to an inflatable kayak with Hydrolite boat mount kit

- Cellular RTK network via a Verizon mobile hot spot

The survey produced the following data points, which will be used in the design:

- Topography and root crown survey points:

- Equipment output: Tabular (CSV) with northing, easting, ground elevation

- Broken out by type (root crown elevation, bridge elevation, dam elevation, etc.) and converted to shapefiles in ArcGIS

- Bathymetry points:

- Equipment output: Tabular (CSV) with northing, easting, transducer elevation, and echo sounder depth reading where applicable

- Post-processing in Excel:

- Bed elevation = transducer elevation minus echo sounder depth reading

- Eliminated points with depth reading less than 9 inches (assumed to be surface echo)

- Eliminated points with depth reading exceeding 10 feet (error / transducer not submerged)

- Manually eliminated other noise points based on manual inspection

- Final points exported as CSV, then converted to shapefile in ArcGIS

Conceptual Design

The engineering design process will progress from conceptual design to 60% designs, followed by 90% designs, and finally construction ready 100% designs. The engineering design process itself will consist of developing grading plans that meet project criteria for inundation frequencies and depths and create the hydraulic connectivity desired.

The FlowWest integrated modeling/engineering process will determine the best way to enhance connectivity and maximize acreage of habitat created to maximize salmonid habitat. The FlowWest design engineering team will produce biddable construction documents and specifications for utilization in future phases of the project. The engineering team will develop grading plans and other design documents sufficient to support environmental compliance, cost estimating, and determination of the construction approach for each site. Simple planting designs will be created to guide and inform revegetation of each project site once earthwork is completed.

These designs will include woody species to be planted from live cuttings (i.e. cottonwood and willows) and native seed mixes to be broadcast across disturbed areas for erosion control and ecosystem benefits. Planting designs will be created to maximize the quality of salmon habitat, including water temperature control and protective cover for juveniles. The planting designs will include species lists, seed mixes and application rates. During construction, engineers will provide site-specific field engineering to ensure the completed projects meet the intent of the designs.

Historical Assessment

FlowWest will complete the historical assessment task by obtaining and analyzing historical ground photos, historical air photos, historical maps, and other documents to determine the history of channel, habitat, and vegetation changes that have happened since the beginning of the Gold Rush. A historical assessment report will be compiled, including findings of the analysis, figures of historical channel morphology floodplain mining activities, and the results of the land use change assessment.

Data

Friends of Butte Creek is developing a monitoring plan for the project site, which will encompass temperature, streamflow, water quality, soil profile, and groundwater monitoring. Collected data will be shared on this page in the future. The test pits for soil profile and groundwater monitoring will be installed as part of the Bridge and Asphalt Removal project.

Analysis

Hydrology

Measured at its downstream outlet, the mine tailings reach of Butte Creek drains a total of 96,718 acres of catchment area. The Butte Creek mainstem extends 49.7 miles upstream to its headwaters above Cirby Meadow in Lassen National Forest, with several significant tributary streams including Willow Creek 1, Scotts John Creek, Jones Creek, Willow Creek 2, Colby Creek. Inskip Creek, Bull Creek, Bolt Creek, Clear Creek, West Branch Butte Creek, and Varey Creek. The distinct eastern tributary stream Little Butte Creek, which enters Butte Creek Canyon just above the mine tailings reach, accounts for 19,143 acre of the total drainage basin.

Butte Creek flows from its headwaters in Lassen National Forest out towards the Sacramento Valley through a series of steep, narrow canyons; the stream cuts through bedrock and creates narrow alluvial terraces. Canyon walls gradually open up approaching the project reach in Centerville, allowing the stream to spread into a wide braided gravel stream system which has since been extensively impacted by mining and dredging.

The Butte Creek mainstream flows used to be heavily modified by the PG&E DeSabla-Centerville Hydroelectric Project through diversions for power generation at the Butte and Centerville Head Dams, and through import of water from the West Branch Feather River via Hendricks Canal and DeSabla Reservoir. As of December 2024, neither Butte or Centerville Head Dams are operational. The only remaining diversion is for the run-of-the-river Forks of Butte Hydroelectric project above DeSabla Powerhouse.

The stream through the project reach is dominated by runs and riffles. Very few pools occur and a limited number of side channel backwaters and overflow channels exist as illustrated below.

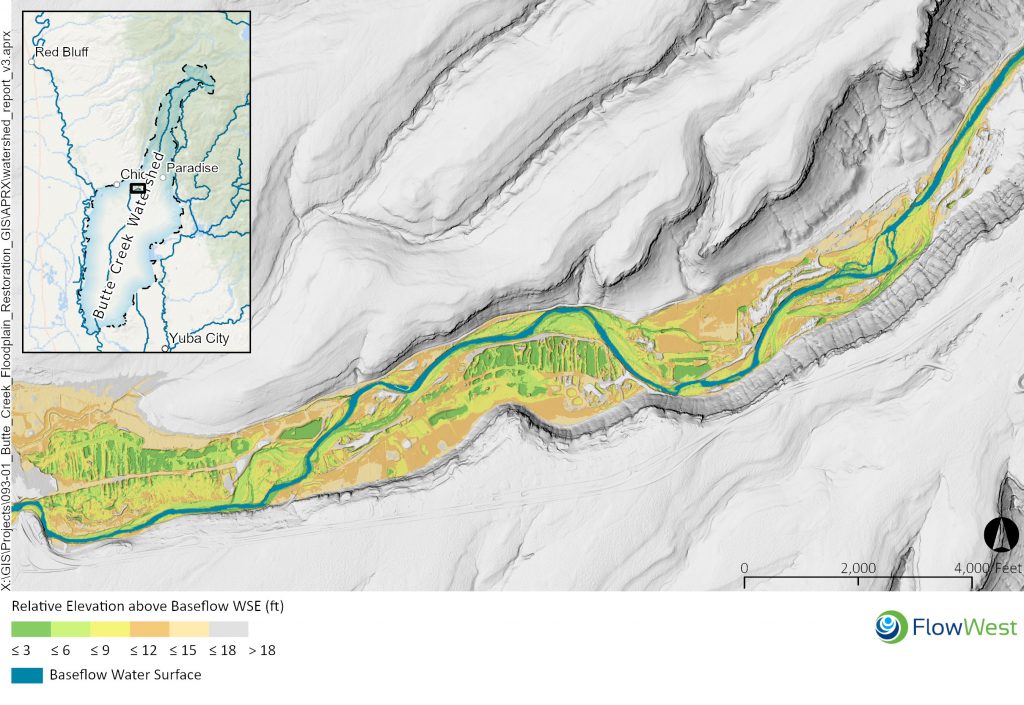

Channel Topography

The following figures illustrate the relative elevation of channel and floodplain topography above the channel. Former tailings and dredge pond areas create low depressions at water level. These features can be recaptured during high flows to alter the course of the river, as occurred in the 1986 floods. Compared to active floodplain areas within the river’s meander belt, these features tend to have relatively low-quality, ruderal habitat with many invasive species. Pools and depressions also create stranding hazards for fish. The most active channel migration areas are visible in the darkest shades, where elevations only slightly exceed that of the adjacent perennial channel. The anabranching channel area at the upstream end of the map formed in 1986 when the main channel avulsed from its former alignment along the left canyon wall and captured a series of gravel mining pits. The reach alongside the large gravel-mined area in the middle of the reach has seen the development of large gravel bars that have stabilized over time.

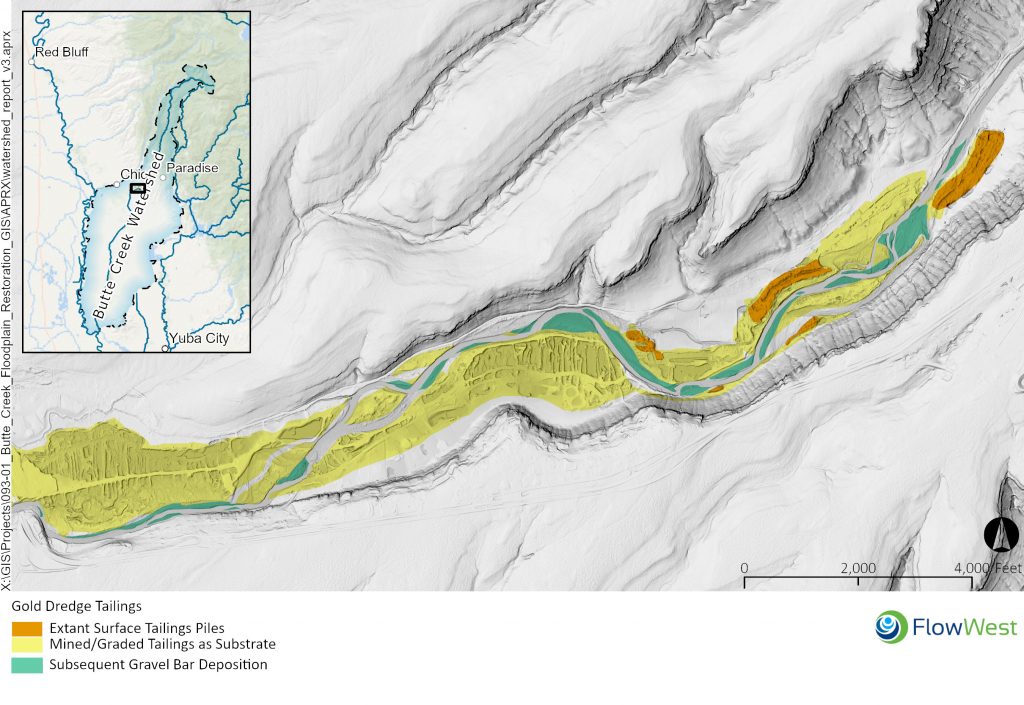

The following map illustrates the spatial extent of gold dredge tailings and gravel bars on the landscape. The mapping of gold dredger tailings distinguishes those that remain intact and those that have been subsequently gravel-mined or otherwise graded. Delineated areas are those where mine tailings were visible in one or more historical aerial images. Those areas that were subsequently scoured by the mainstem creek channel through avulsion are excluded. (For more detail, the accompanying historical assessment traces the distribution of tailings throughout many historical timepoints based on aerial imagery and topographic maps.) Extant gravel bars are also mapped. These gravel bars are relatively recent landforms that appeared in more recent historical imagery after gold dredging had ended.

Vegetation

Vegetation along the project reach varies from high-quality riparian woodland to, more extensively, opportunistic ruderal vegetation that has established on dredge tailings. Supplemental baseflow from the Feather River diversions keeps water tables higher year-round, allowing more establishment of groundwater-dependent riparian vegetation at higher relative elevations within the floodplain (Harthorn 2002).

The site combines a relatively high-gradient and avulsion-prone natural flow regime with a highly modified post-dredging landscape. The resulting distribution of vegetation Is complex. As Oswald (1997) notes in a description of the upstream Butte Creek Ecological Preserve, “[d]uring periods of high run-off, some of the flow of Butte Creek follows a channel through the tailings, carving some deep ponds and leaving behind fresh deposits of mud, sand, and gravel. Seeds of a number of plants that normally grow at higher elevations in the watershed are also left behind, which results in some rather unusual plants . . .” (Oswald, 1997).

Documents

| Category | Title |

|---|---|

| Outreach | Project Outreach Poster |

| Historical | Butte Creek Watershed Project Existing Conditions Report |

| Historical | Geomorphic Assessment of Butte Creek |

| Historical | NOAA 2014 Recovery |

| Project Resources | Site Assessment in the Watershed Context |

| Project Resources | Monitoring Plan (coming soon) |

| Similar Projects | Middle Klamath – Legacy Placer Mining Restoration |

| Similar Projects | Merced Ranch |

Additional Air Photos

All Rights Reserved